A pediatrician holding a dose of the MMR vaccine. (Photo by Damian Dovarganes)

What it takes to get exempted

If a child does not meet state requirements for vaccination without an exemption, they are at risk of losing their ability to remain enrolled in school. Massachusetts only offers two kinds of vaccine exemptions: religious and medical, the latter requiring a physician’s sign-off.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), some of the reasons allowing for medical exemptions may include allergies, autoimmune diseases or chemotherapy treatments, which weaken the immune system’s ability to fight against the side effects of a vaccine.

“It’s sort of funny terminology, because we can only think of two religions that actually have an exemption. So, it’s really more of an ideological exemption than a religious exemption,” said Peter Dillon, superintendent of the Berkshire Hills Regional School District.

According to a 2013 study by John Grabenstein for the journal “Vaccine”, the only legitimate theological objections to vaccines were held by the Dutch Reformed Church and Christian Scientists, though they express respect for those who do seek vaccines out. The rest is a grey area, although many leaders in large religions have generally encouraged vaccinations. During the COVID-19 pandemic, Pope Francis determined getting vaccinated to be a “moral obligation”.

Even so, the process of obtaining a religious exemption is not a difficult one.

The future of religious exemptions has been up in the air for nearly seven years now, explained Katie Blair, director of Massachusetts Families for Vaccines, an advocacy group whose focus lies on various pro-vaccine policies. Blair explained that the group has been focused on supporting bills like Massachusetts House Bill H.604 and S.1391, which aim at removing the non-medical exemption.

“To be honest, the fact that we are still talking about this is embarrassing,” said Janna Koretz, psychologist and mother to a child with complex medical needs, who was testifying in support of the bill H.604 for the fourth year in a row. “For my family, having someone opt out of vaccines for so-called religious reasons is no different than them choosing to be above the law and drive drunk and kill someone. The effect is the same for us.”

“If you live in a society, you have to follow rules. If there are loopholes for this rule, there can be loopholes for other rules, and then more people will die,” reiterated Koretz.

There is little room for schools to dispute religious exemptions, even if there is no way to cite vaccine hesitancy as being attributed to a sincere tenet of an individual’s religion. The implication, then, turns to politics.

“A tricky position for pediatricians”

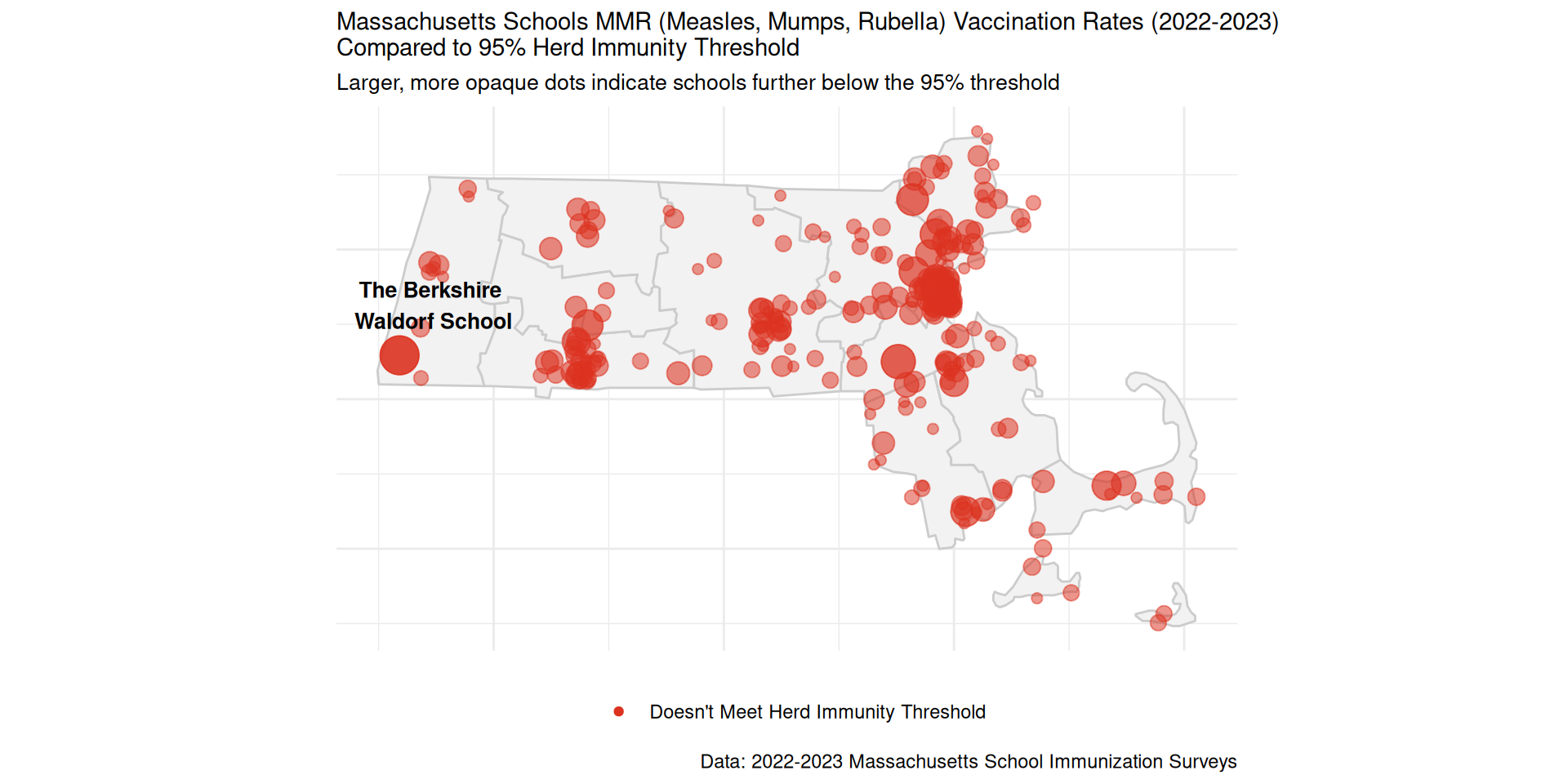

The political makeup of western Massachusetts is varied, red bubbles like Southwick bracketed on all sides by blue. “This is a place where the far right and the far left sort of come together, and on both ends, they’ve got concerns about [vaccines],” said Dillon.

Pediatric physician and hospitalist at Cooley Dickinson Hospital Jana Cable also emphasized that personal philosophy may be masquerading in the form of a religious exemption, though politics don’t tell the whole story. In Cable’s experience, scientific misunderstanding ultimately plays the largest factor in parents’ vaccine hesitations.

“When a kid’s parents don’t want to vaccinate, it’s a tricky position for pediatricians to be in,” she said. “Usually, if you show them the scientific evidence and talk about the benefits of being vaccinated, they’ll change their mind, but not everyone is open to discussion.”

She described apps like YouTube, TikTok and Instagram as being key players in the spread of medical misinformation, but especially vaccines. “In the moment, it can seem like you’ve discovered this area that the mainstream media isn’t talking about. […] So, I can see how families get sucked into it,” she said. “Sometimes I think these sources could be doing even more damage than the current administration is.”

Up until the recent spate of outbreaks across the U.S., director of Health and Human Services Robert F. Kennedy Jr. had been loudly against vaccinations. In a video from February, Kennedy said, “You may be killing more [children with the measles ‘vaccine’] over the long run than measles ever did.” However, at the beginning of April, his rhetoric appeared to shift following a visit with a family in Texas whose child had died of measles. He wrote on ‘X’ (formerly Twitter), “The most effective way to prevent the spread of measles is the MMR vaccine,” prompting backlash from a subset of the anti-vaccination movement.

Footage from the February 2025 premiere of The Big Picture on CHD.TV. (Video via CHD.TV)

“The irony is that public health has been so successful that it’s actually lulled people into thinking that they don’t need public health vigilance,” said Dorit. “When people say COVID is like the flu, yeah, now it is. Now that everybody, you know, has either been vaccinated or has had COVID, it’s more like the flu. At the beginning, it was far more dangerous than the flu.”

Children in-between: incomplete vaccines without an exemption

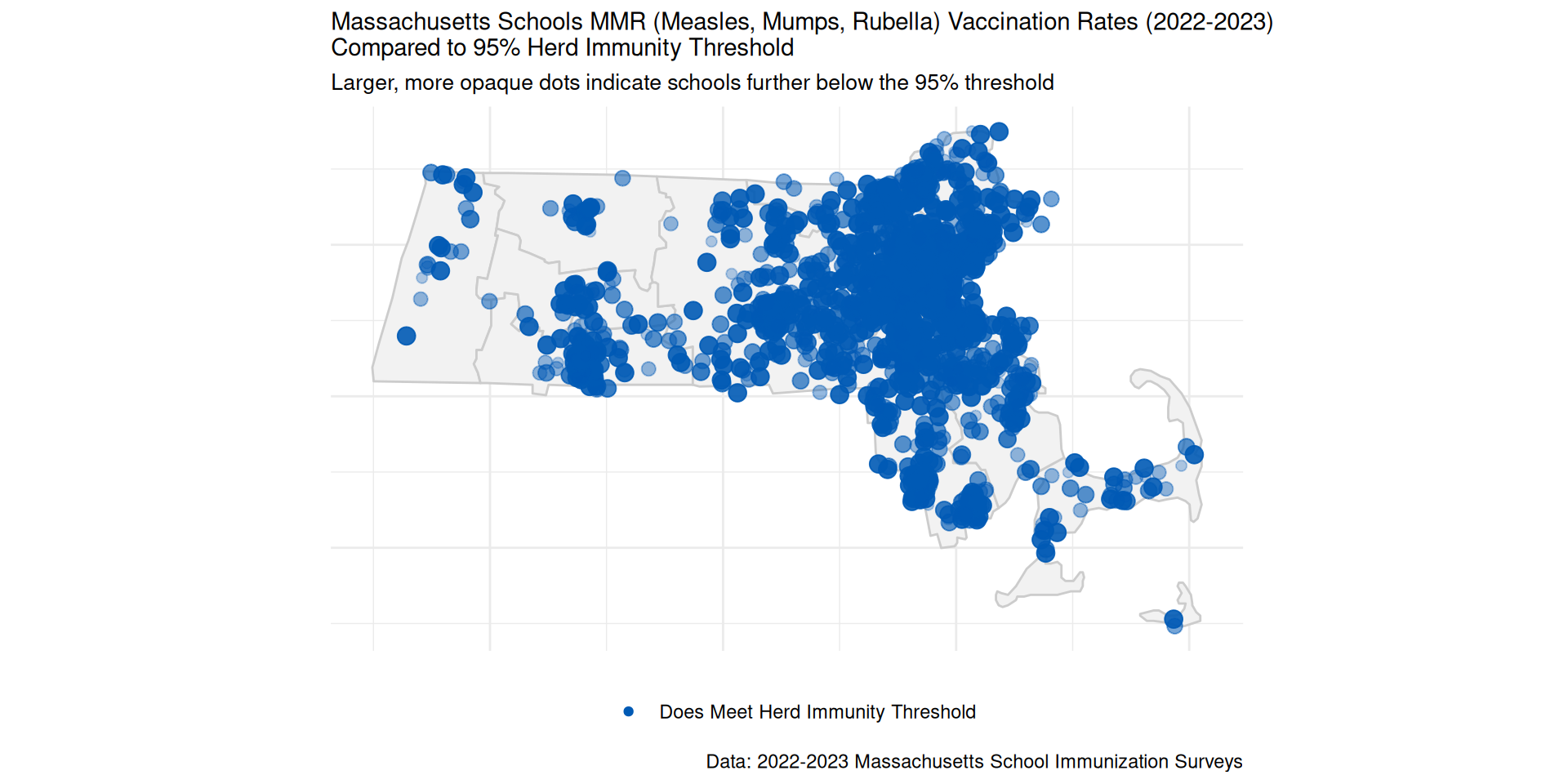

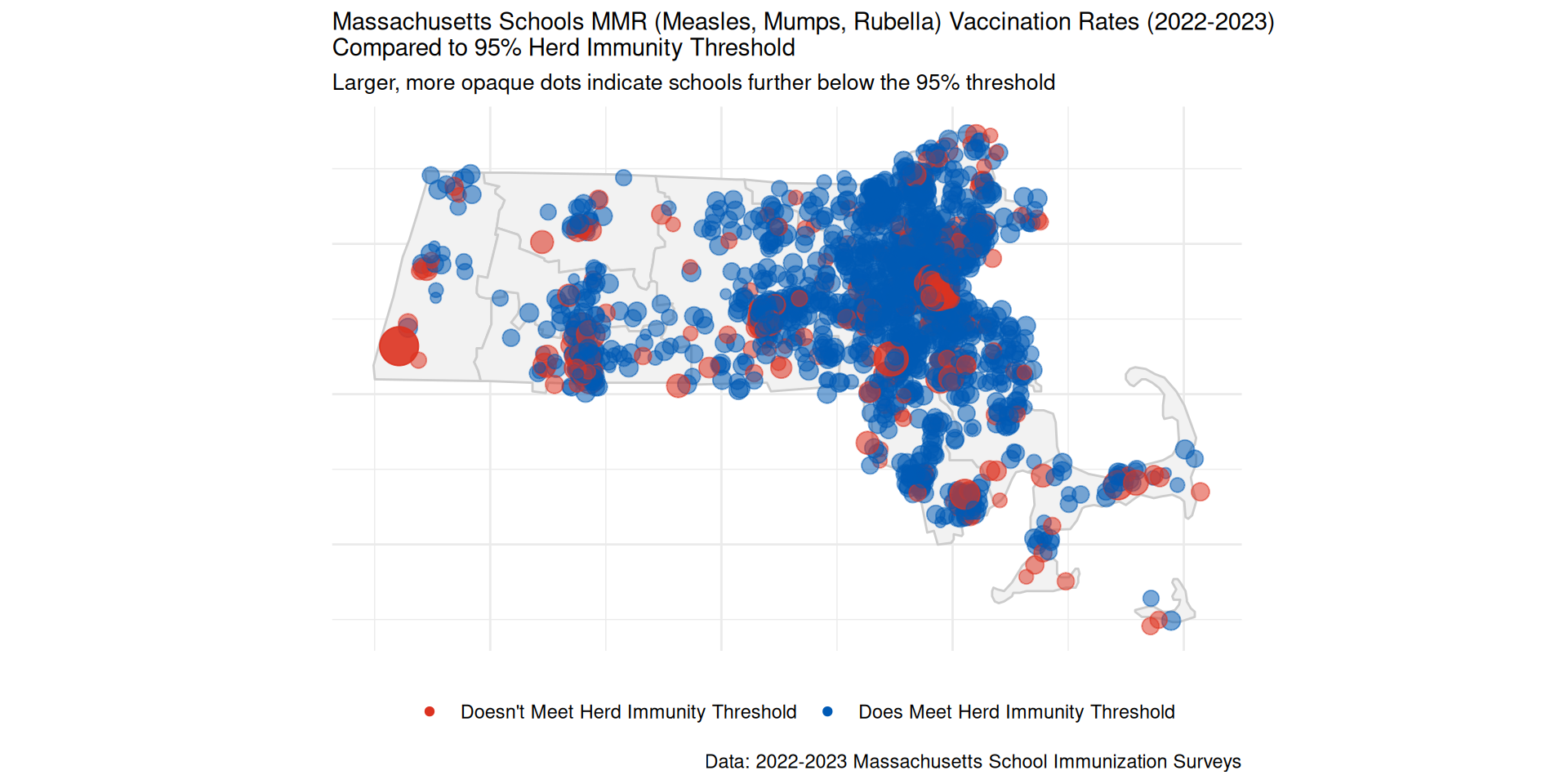

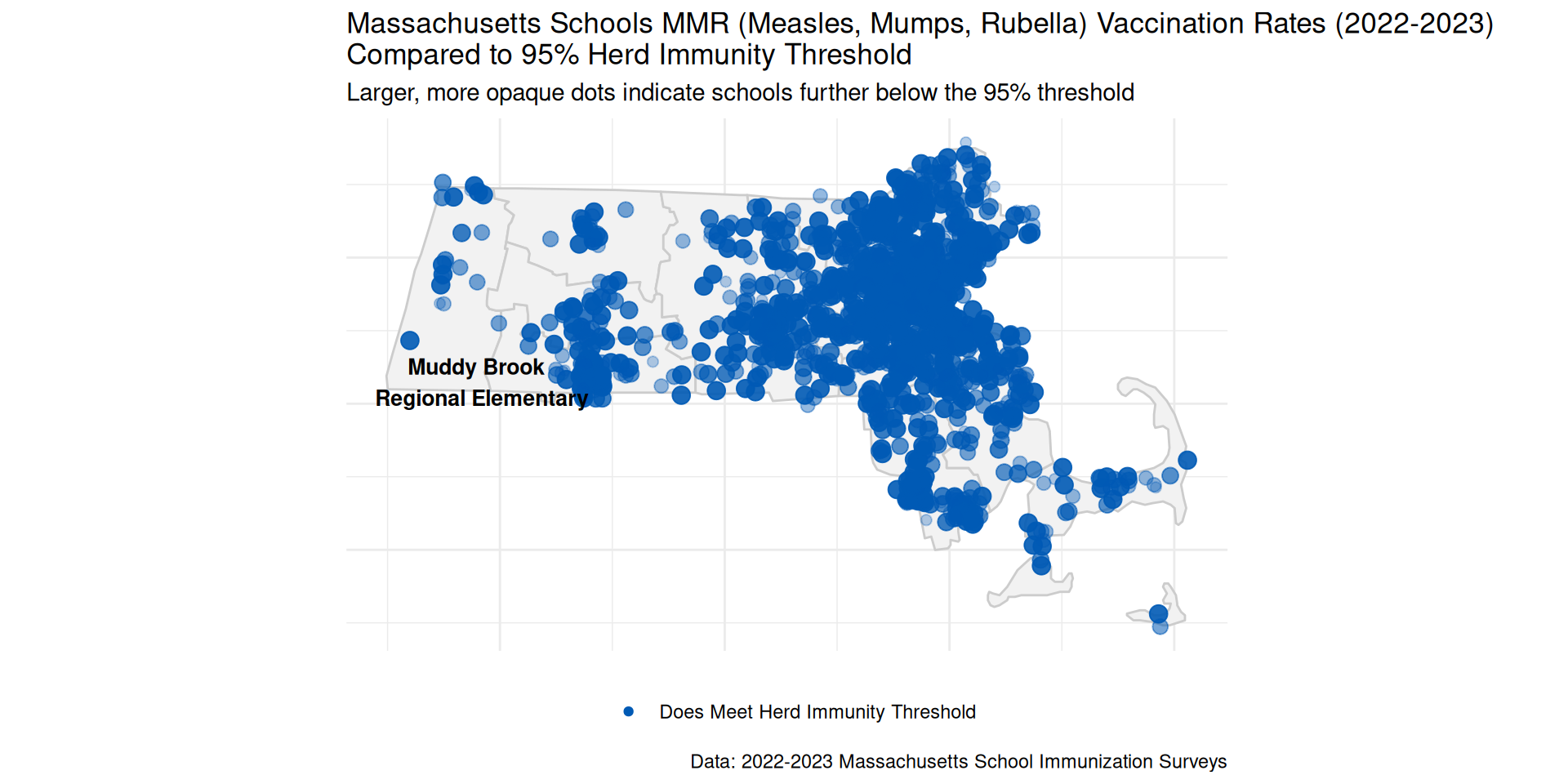

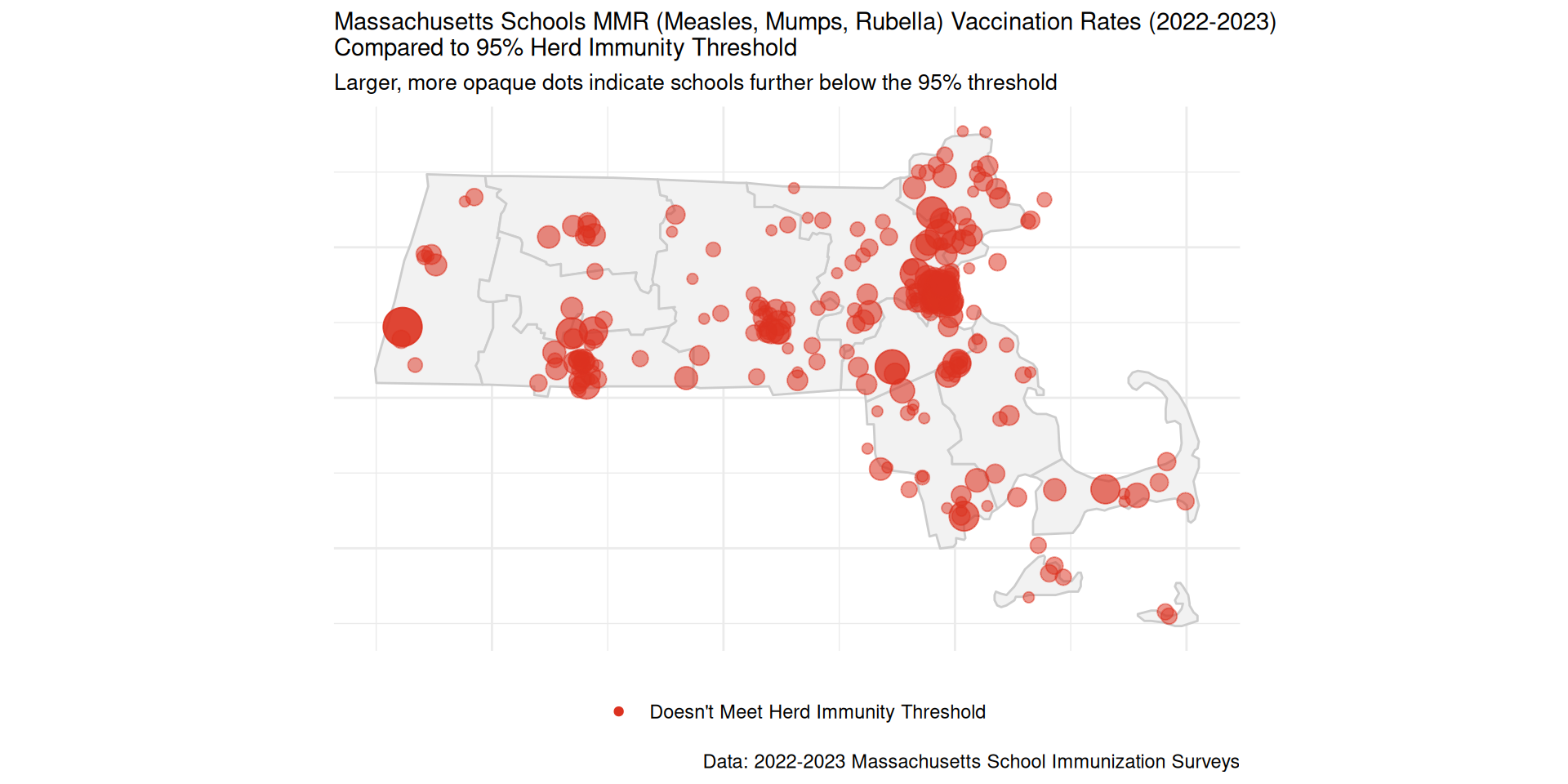

As of 2023, Berkshire, Franklin, and Hampden counties account for some of the highest rates of unvaccinated preschool and kindergarten-aged children in Massachusetts who do not maintain a medical or religious exemption. These students fall into the “gap” of undocumented vaccination information, meaning that even if they have been immunized, their schools have no record of it. Berkshire county maintains the highest gap percentage (8.7%) of the whole state, which has a cumulative gap rate of 4.6%.

The reason for this gap is difficult to pin down. First, experts say reported immunization data usually does not capture an entire school year. Some data is also missing; schools with less than 30 students per class year are not required to report immunization data to the state, which according to experts, allows for a margin of error.

Difficulty getting into a doctor’s office may not be limited to recently-immigrated families. The Center for Health Information Analyses (CHIA) found in a 2023 survey that 41% of Massachusetts residents had difficulty getting an appointment at doctors offices or clinics, a phenomenon that has been gradually worsening since the COVID-19 pandemic. To Dillon, the issue may be geographically specific.

“People talk a lot about food deserts in urban communities, when people don’t have access to fresh food, right? With determinants of health, there’s certainly a similar lack of access — or there are really long waits,” said Dillon. “That could be to see a pediatrician, a counselor, a psychologist or a social worker, whether it’s for themselves or for their kids.”

However, Cable doubts that vaccine rates have been directly impacted by medical shortages in western Massachusetts.

“There’s certainly a primary care shortage, which is multifactorial, but to my knowledge it hasn’t affected pediatrics as much as it’s affected adult care,” said Cable. “Most practices really try to get kids in for wellness checks and immunizations – it’s a big priority.”

The reason behind this prioritization is what Dorit called the “immunological memory” of human beings.

“Kids are fairly immunologically naive,” he said. “Your immune system has what seems like a completely unreasonable task, which is to recognize everything that is in your body, circulating in your mucous membranes, that shouldn’t be there.”

Because children have short immunological memories, the number of vaccines that young children need to receive is much higher than older kids, teenagers and adults. Some are one-and-done, but others need regular booster shots. A measles vaccine is typically a once in a lifetime vaccine, but since the disease’s re-establishment in the U.S., Dorit said, “there are wrinkles now.”

What is being done

Ultimately, the ability of physicians and school administrators to protect children from infectious disease is limited by their roles.

“Our goal is to support all kids and families,” said Dillon. Some infectious diseases have longer excusal days than others, given the cycle of the disease. “It’s advantageous if they’re in school, but we’re also cognizant of exposure.”

In the event of an outbreak, any parents with children exempted from the full vaccination circuit — or children who do not meet all requirements — must be contacted by the school. Such was the case at Muddy Brook when one child contracted chicken pox.

“We just called all the families with exemptions and said, ‘You can either keep them home days 10 to 21 after exposure, or you can go to the doctor within the next five days.’ Which everyone did,” said Touponce.

A 2024 CDC survey aimed at assessing parents’ attitudes, experiences, and knowledge regarding vaccination requirements and exemptions found that over 30% of parents and guardians surveyed agreed that unvaccinated children should be allowed to attend school or daycare. This finding reflects a broader debate about vaccination requirements and their impact on children’s education. While most parents support enforcing vaccination policies, there is concern about the consequences of excluding children from school or daycare.

A child who contracts measles must be kept out of school for at least 20 days to minimize potential spread. “I imagine some number of people that have religious exemptions would at that point entertain getting their child immunized, because 20 days of not going to school is like a month not going to school, and it would be very hard to manage that if you had a little kid and you were working, right? In a traditional, like a go-to work kind of place, it would be very hard to do that,” said Dillon.

The impact of exclusion periods can vary greatly based on the individual circumstances of each family. For some, the disruption caused by these periods is met with open arms due to their flexible schedules. Yet for others, these periods simply add on additional financial and logistical challenges.

As Northe Saunders, Executive Director of the Safe Communities Coalition, emphasized in the 2023 public hearing: “Parents shouldn’t have to worry about an outbreak of measles, whooping cough, or chicken pox shutting down their school. Parents have to miss work when kids have to be kept home. The knock-on effect of vaccine preventable diseases outbreak can cost hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of dollars. Without strong vaccine laws, not only do our kids get sick, but our economy suffers.”

While strong vaccine regulations have repeatedly proved to prevent outbreaks and protect public health overall, Cable acknowledged that it is crucial to not forget what lies at the center of these deliberations.

“At the root of all of this is parents wanting to be good parents,” said Cable. “We have to be okay meeting them where they’re at. Regardless, we’re going to care for their kid even if they don’t follow our recommendations.”