To avoid inaccurate judgement based on visual identification, law enforcement has long employed field drug testing. But inaccuracies in field drug testing may be hamstringing the ability of police to fairly meet the law, as well as wasting resources, data shows.

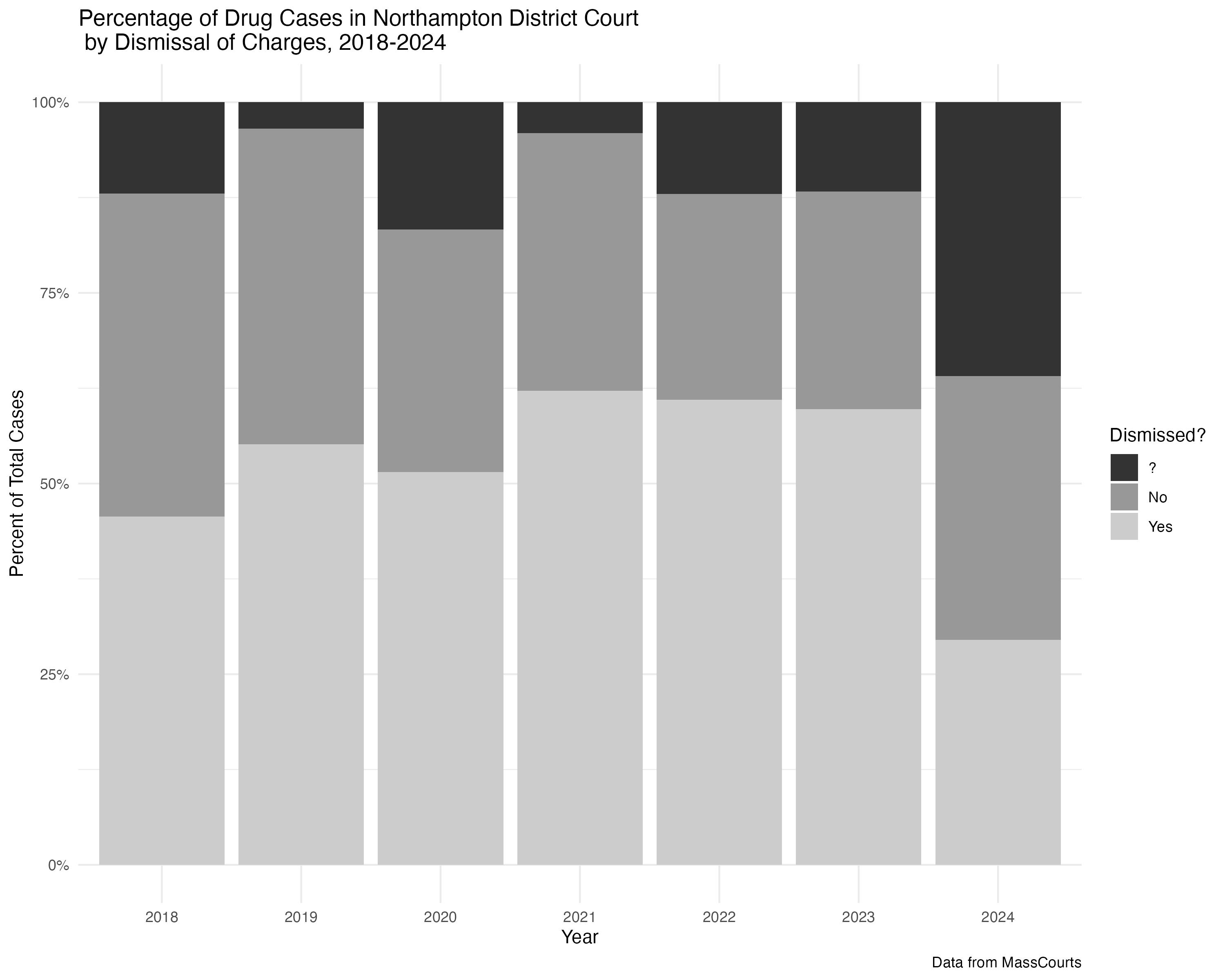

The overall failure of these charges to result in convictions raises questions about the drug arrest procedures, namely the reliability of the testing process – not just in the field, but even once substances are sent to the lab, experts say.

“I think [the drug testing process] is a huge scam,” said Luke Ryan, a Northampton based public defender who has represented clients subjected to chemical drug testing.

“[Drug testing] is not DNA, it is not a science, it is a process, but it’s not one that has the same scientific principles behind it.”

Field drug testing is a method of chemically testing drugs at the time of an arrest, allowing officers to use presumptive identification to send substances to a lab for further testing. In a car stop, the police will test a suspected narcotic and arrest on the charge of drug possession.

According to a 2024 study by University of Pennsylvania’s Carey Law School, field drug testing is one of the most common factors leading to wrongful arrests and convictions, resulting in 30,000 false accusations yearly. “Presumptive field drug test kits are known to produce ‘false positive’ errors and were never designed or intended to provide conclusive evidence of the presence of drugs,” says Ross Miller, author of the report.

Field drug tests are done on-site of a suspected crime or search, said Detective Sergeant Patrick Moody, an officer of the Northampton Police Department (PD). Equipment is available at the station for patrol officers to take out, and also kept in police cruisers.

“If we saw [a suspected bag of cocaine] on the passenger floor of a car, we would take the driver out, ask them about it, and at that point we would be able to search the car…Then we would go through the field-testing process and articulate how we know what it is,” said Moody. “It is a presumptive test, so based on our training experience and the test…we can charge the person with possession of cocaine.”

The process itself is simple, designed to work quickly, he said. “[The field drug tests] are just basically plastic devices with glass cylinders in them,” Moody said. “We put the sample on the end of [the stick], and then put the sample down into the delivery system…then it should have a color to determine if it is positive or not. The results will usually show up in specks, where the little pieces fell, because you cannot put that much on there.”

“[The field drug tests] are just basically plastic devices with glass cylinders in them,” Moody said. “We put the sample on the end of [the stick], and then put the sample down into the delivery system…then it should have a color to determine if it is positive or not. The results will usually show up in specks, where the little pieces fell, because you cannot put that much on there.”

The National Institute of Standards and Technology argues presumptive field tests provide an efficient way for police to quickly and safely test suspicious contents without the equipment and labor of full lab testing. Yet, the UPenn report found a 32% false positive rate in drug field testing, from methamphetamine to cannabis, in the Massachusetts State Department. The Massachusetts Department of Corrections themselves noted a 38% false positive rate, which they ruled is only marginally better than a coin flip.

This could be in part due to the physical design of some field drug tests. “The only [difficulty] is it is hard to get [the stick] out and it is the same thing to get it in there. I mean there is a lot of room for contamination where you could drop [the substance] out or it would pop out,” said Moody.

The use of field drug testing has been questioned in trials numerous times both before and after the Farak scandal. It was officially implemented in 2017 in the Massachusetts Department of Corrections as a novel tool to prevent misconduct and as an additional step to improve the process of drug arrests.

Yet when it was Ryan’s turn to cross-examine the new drug testing process in 2014 in the Hampshire County Superior court case of Commonwealth v. Wayne Burston, he said he questioned the company Sirchie, which was campaigning the efficiency of the field drug tests the state was bidding on. Specifically, Ryan challenged the technical details of their use. According to Ryan, he said to a representative of the company after they demoed the field drug process, “‘I’m going to give you a piece of chalk, will you go up and explain the science behind why that happened,’ and [the representative] just handed the chalk back, and said ‘I’ve got nothing for you.’”

Drug arrests are costly to the city, from hours dedicated to officer training, to the testing process itself. In 2018, the John Hopkins School of Public Health investigated the costs of simple drug possession crimes in Baltimore City. They found the cost to the city per individual arrested was an average of $3,600. With trial, the cost ballooned to an average of $6,000. While overall costs of arrests and trials may vary in Massachusetts and based on population, Northampton is spending thousands of dollars on each individual arrest. Based on arrests in 2023, the city could have spent up to $170,000 that year for drug arrests that did not end in a conviction, or up to $282,000 for arrests leading to trials without conviction. Northampton police receive the majority of their funding from municipal taxes, meaning resident income is potentially going towards false arrests and accusations for drug possession crimes.

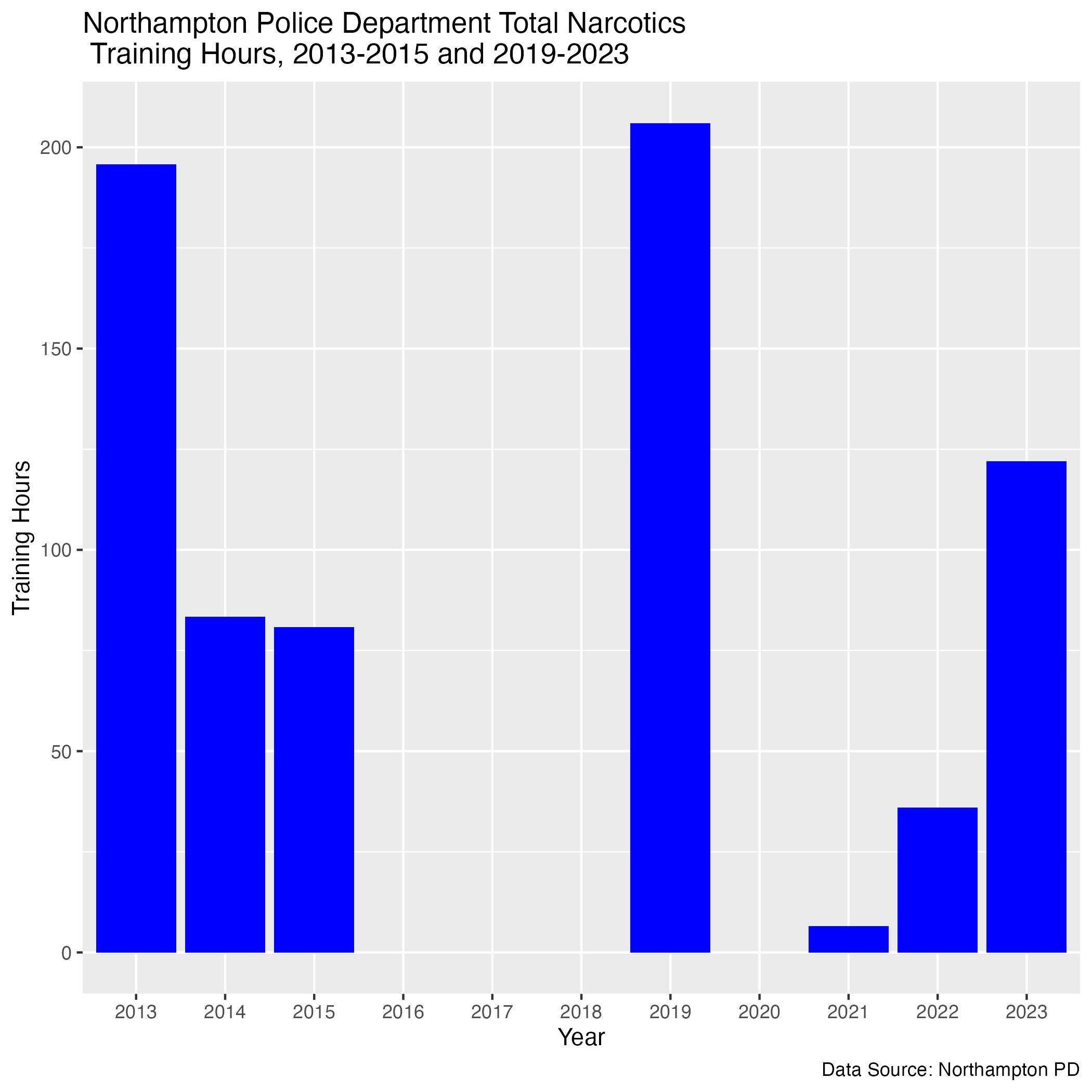

While not the ones conducting full chemical drug tests, police training surrounding narcotics arrests and investigations plays an important role in kickstarting the lengthy process of convicting someone for drug crimes. “The training you receive for narcotics is off-site,” said Detective Moody. “I’ve been to numerous training sessions where you actually see the drugs, handle the drugs, learn how to test them, learn how to identify them, learn how they are packaged, how they are used, and how they are sold.”

The changing landscape of drug testing technology and the nature of promotions can result in police losing track of the skills taught in narcotics training. “One of the downfalls of being promoted out of the Detective Bureau is that you lose a lot of the skills and training that you acquired before,” said Moody, “and technology advances very fast, especially in this job.”

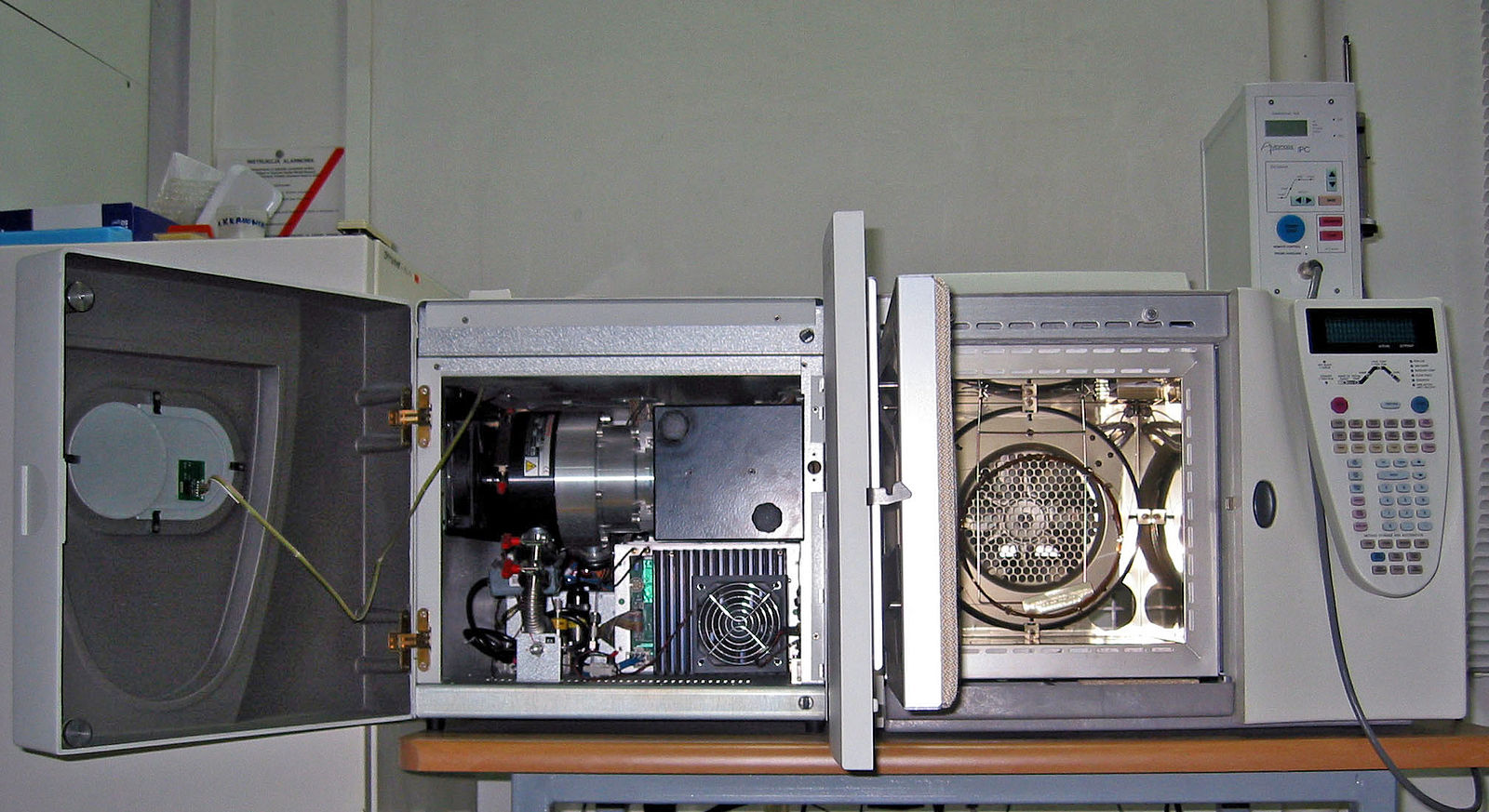

There are many steps between the process of the seizing of a supposed narcotic to the point it is shown in court. After an arrest, an employee will check the substance into evidence where it will sit in a storage locker before it is sent to the Springfield drug lab. At this point, the chemists will be assigned the samples to test and execute a confirmatory test using machines. The second level of testing is more sensitive, and is used to confirm a specific drug.

However, even in the lab, the process of chemical testing of drugs is error-prone. “If you ran [the same substance] through the machine in 15 minutes, it would be slightly different even though it is the same substance,” said Ryan.

Northampton’s focus on drug crime in Northampton has not changed. The number of drug cases reported in court records has remained stable from 2018 to 2024, averaging about 78 cases a year regardless of disposal status, and major crimes continue to be rare.

Beyond the potential strains on police and community resources, people in Northampton are impacted in long lasting ways by erroneous drug testing.

“There are some people that their lives get disrupted, but these are more often people who are unhoused or hanging outside a lot and police come and that can further complicate an already complicated situation,” said Dan Bickford, a peer coordinator at the Northampton Recovery Center. “Sometimes that can lead to incarceration…sometimes that can be beneficial for someone, other times that’s just more resentment towards the systems.”

One of Ryan’s clients was Rafael Rodriguez, who was sentenced to two and a half years based upon Farak’s chemical tests and filed to have those charges amended. Rodriguez was initially arrested on a charge of cocaine possession to distribute, and taken away from his children and wife based on these claims. After serving a series of prison sentences, Rodriguez struggled to find stable work and eventually began to seek illicit substances, according to a Rolling Stone profile of Luke Ryan.

“But before the case got resolved,” Ryan said, “he overdosed and died. The biggest impact on [clients] was the loss of liberty, the loss of livelihood, the loss of connections with loved ones. People’s immigration statuses were impacted. People lost access to public housing.”

Misconduct during the drug testing process would have been enough to have the charges voided, regardless of Rodriguez’s drug use outside of the initial cocaine possession charge, which couldn’t be confirmed due to Farak’s tampering, demonstrating the potential devastating impacts of inaccurate testing beyond wasted resources.

However, some feel supported by the Northampton PD’s involvement with drug crimes. “[Run-ins with law enforcement] go along with the territory unfortunately. Especially if you’re passed out, but you know I have not heard any horror stories, and most of the time I believe people are pretty respectful,” said Deb Boudreau, a Northampton Recovery Center coach. “It’s a good town, and I think they support the best they can.”

The continued use of erroneous drug testing in Northampton despite its demonstrated risks is representative of a larger systemic issue in the criminal justice system, one that continues to target and harm the lives of those in the local community. “The drugs we criminalize, we don’t criminalize because of what they do to people, but we criminalize them because of the people we associate them with,” said Ryan. “I’m not interested in tweaks to a system that just needs to stop. If the original prohibition was called the noble experiment, this is the ignoble. We know it doesn’t work.”

References

- Miller, R., Heaton, P., & Sturges, H. (2023). Guilty until Proven Innocent: Field Drug Tests and Wrongful Convictions. University of Pennsylvania Quattrone Center for the Fair Administration of Justice. https://www.law.upenn.edu/live/files/12890-fdt-guilty-until-proven-innocent

- Rouhani, S., Tomko, C., Silberzahn, B., Sherman, S., & Cepeda, J. (2023). Estimating economic costs of prosecuting simple drug possession in Baltimore City. John Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. https://americanhealth.jhu.edu/sites/default/files/estimating-economic-costs-prosecuting-simple-drug-possession-baltimore-city-april-2023.pdf

- Solotaroff, P. (2018, January 3). And Justice For None: Inside Biggest Law Enforcement Scandal in Massachusetts History. Rolling Stone Magazine. https://www.rollingstone.com/culture/culture-news/and-justice-for-none-inside-biggest-law-enforcement-scandal-in-massachusetts-history-253708/